|

Magnetic level

gauge combines

float technology

with level gauge

simplicity

(Hawk). |

Many industrial processes require the accurate measurement of fluid or solid (powder, granule, etc.) height within a vessel. Some process vessels hold a stratified combination of fluids, naturally separated into different layers by virtue of differing densities, where the height of the interface point between liquid layers is of interest.

A wide variety of technologies exist to measure the level of substances in a vessel, each exploiting a different principle of physics. This chapter explores the major level-measurement technologies in current use.

Level gauges

Level gauges are perhaps the simplest indicating instrument for liquid level in a vessel. They are often found in industrial level-measurement applications, even when another level-measuring instrument is present, to serve as a direct indicator for an operator to monitor in case there is doubt about the accuracy of the other instrument.

Float

Perhaps the simplest form of solid or liquid level measurement is with a float: a device that rides on the surface of the fluid or solid within the storage vessel. The float itself must be of substantially lesser density than the substance of interest, and it must not corrode or otherwise react with the substance.

|

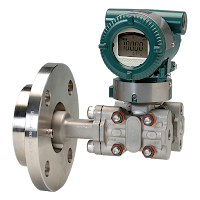

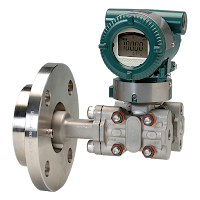

Hydrostatic level instrument to tank

wall mounting (Yokogawa). |

Hydrostatic pressure

A vertical column of fluid generates a pressure at the bottom of the column owing to the action of gravity on that fluid. The greater the vertical height of the fluid, the greater the pressure, all other factors being equal. This principle allows us to infer the level (height) of liquid in a vessel by pressure measurement.

Displacement

Displacer level instruments exploit Archimedes’ Principle to detect liquid level by continuously measuring the weight of an object (called the displacer) immersed in the process liquid. As liquid level increases, the displacer experiences a greater buoyant force, making it appear lighter to the sensing instrument, which interprets the loss of weight as an increase in level and transmits a proportional output signal.

Echo

|

| Radar level transmitter (Hawk). |

A completely different way of measuring liquid level in vessels is to bounce a traveling wave off the surface of the liquid – typically from a location at the top of the vessel – using the time-of-flight for the waves as an indicator of distance, and therefore an indicator of liquid height inside the vessel. Echo-based level instruments enjoy the distinct advantage of immunity to changes in liquid density, a factor crucial to the accurate calibration of hydrostatic and displacement level instruments. In this regard, they are quite comparable with float-based level measurement systems. Liquid-liquid interfaces may also be measured with some types of echo-based level instruments, most commonly guided-wave radar. The single most important factor to the accuracy of any echo-based level instrument is the speed at which the wave travels en route to the liquid surface and back. This wave propagation speed is as fundamental to the accuracy of an echo instrument as liquid density is to the accuracy of a hydrostatic or displacer instrument.

Weight

|

Level can be determined by

weight using load cells (BLH). |

Weight-based level instruments sense process level in a vessel by directly measuring the weight of the vessel. If the vessel’s empty weight (tare weight) is known, process weight becomes a simple calculation of total weight minus tare weight. Obviously, weight-based level sensors can measure both liquid and solid materials, and they have the benefit of providing inherently linear mass storage measurement. Load cells (strain gauges bonded to a steel element of precisely known modulus) are typically the primary sensing element of choice for detecting vessel weight. As the vessel’s weight changes, the load cells compress or relax on a microscopic scale, causing the strain gauges inside to change resistance. These small changes in electrical resistance become a direct indication of vessel weight.

Capacitive

Capacitive level instruments measure electrical capacitance of a conductive rod inserted vertically into a process vessel. As process level increases, capacitance increases between the rod and the vessel walls, causing the instrument to output a greater signal. Capacitive level probes come in two basic varieties: one for conductive liquids and one for non- conductive liquids. If the liquid in the vessel is conductive, it cannot be used as the dielectric (insulating) medium of a capacitor. Consequently, capacitive level probes designed for conductive liquids are coated with plastic or some other dielectric substance, so the metal probe forms one plate of the capacitor and the conductive liquid forms the other.

Radiation

Certain types of nuclear radiation easily penetrates the walls of industrial vessels, but is attenuated by traveling through the bulk of material stored within those vessels. By placing a radioactive source on one side of the vessel and measuring the radiation reaching the other side of the vessel, an approximate indication of level within that vessel may be obtained. Other types of radiation are scattered by process material in vessels, which means the level of process material may be sensed by sending radiation into the vessel through one wall and measuring back-scattered radiation returning through the same wall.

Power Specialties Sales Engineers are experts in industrial level control. Feel free to contact them at (816) 353-6550, or by visiting

http://www.powerspecialties.com, for any level application. They'll assure you get the best continuous level control for the application.

Content above abstracted from “Lessons In Industrial Instrumentation”

by Tony R. Kupholdt under the terms and conditions of the

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License.